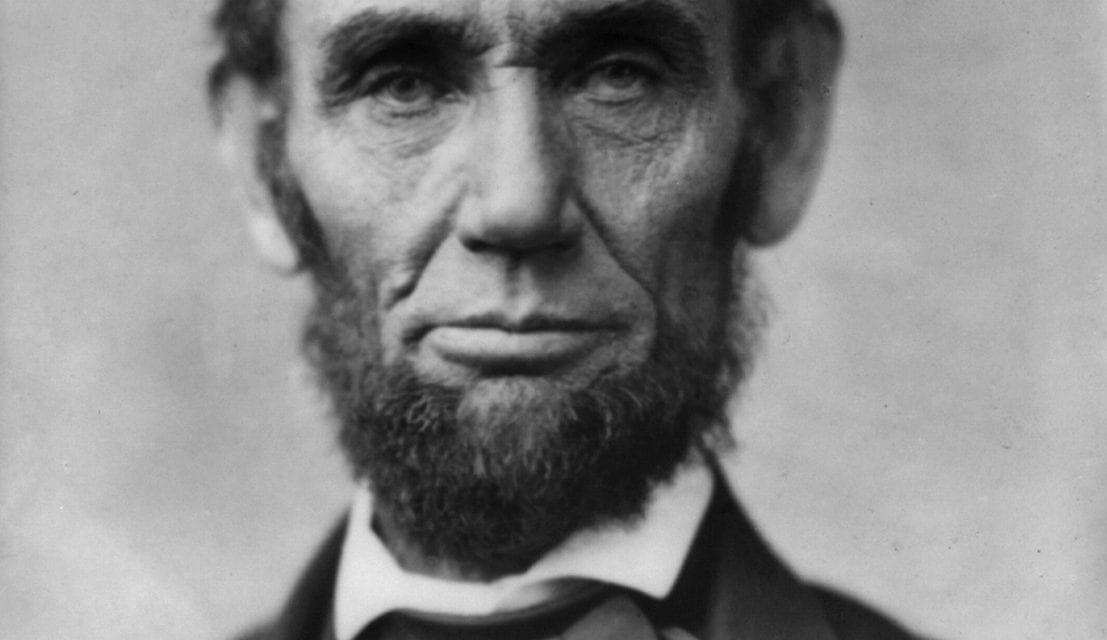

Abraham Lincoln was elected president of the United States largely because he was a rail-splitter.

At the time he was elected, he had not split a rail for nearly thirty years. His rail-splitting had been done when he was a young man; at a time when there was no way for him to know it would one day help make him President.

There is abundant proof that Lincoln had a dream he might one day become president, but there is no way he could have known that splitting logs would have any bearing upon his election.

Lincoln’s splitting of rails, and his subsequent election to the presidency, may be used to illustrate any number of themes, but the lesson which comes through most clearly is that the faithful doing of trivial duties in childhood or adulthood may have an important bearing upon later events of greater significance.

Splitting Rails to The White House

The rails that elected Lincoln to the presidency were old and moss-grown by the time they were called into service for their share in the glory of Abraham Lincoln’s presidential campaign.

For thirty years they had done service as part of a fence. They were, as the placard which they bore attested, “Two rails from a lot of 3,000 made in 1830 by John Hanks and Abe Lincoln.”

Some of those 3,000 rails were locust and some were walnut. They were rived in Macon County, Illinois, about ten miles from Decatur. But for those rails, it is very unlikely that Abraham Lincoln would ever have been nominated for the presidency.

When the Campaign of 1860 began, Abraham Lincoln was little known outside his own State of Illinois, and was far from being the unanimous choice of even his own State for the presidency.

He had won wide recognition for his debates with Stephen A. Douglass, and his Cooper Union speech had introduced him to New York City, but few of the men who were to decide on the Republican candidate for president had seriously considered Lincoln as the logical candidate.

Illinois itself was divided. The northern part of the state was largely for Seward, and the southern part for Lincoln, but the northern part of the state, which included the growing city of Chicago, where the Republican National Convention was to be held, was highly important in the upcoming election.

Lincoln wrote to his friend Norman B. Judd in Chicago, saying,

The state convention was held in Decatur on May 9th and 10th. Lincoln attended. He told his friends that he was too much of a candidate to be present and not quite enough of a candidate to justify him staying away.

It was possible to succeed in the state meeting and fail in the national assembly, but it was certain that if he failed to secure the united backing of his own state at Decatur, his presentation as a candidate in Chicago would merely put him in the same category of others who were to have their names presented with no real expectation of a nomination. If he was to have success in Chicago, Lincoln must succeed in Decatur.

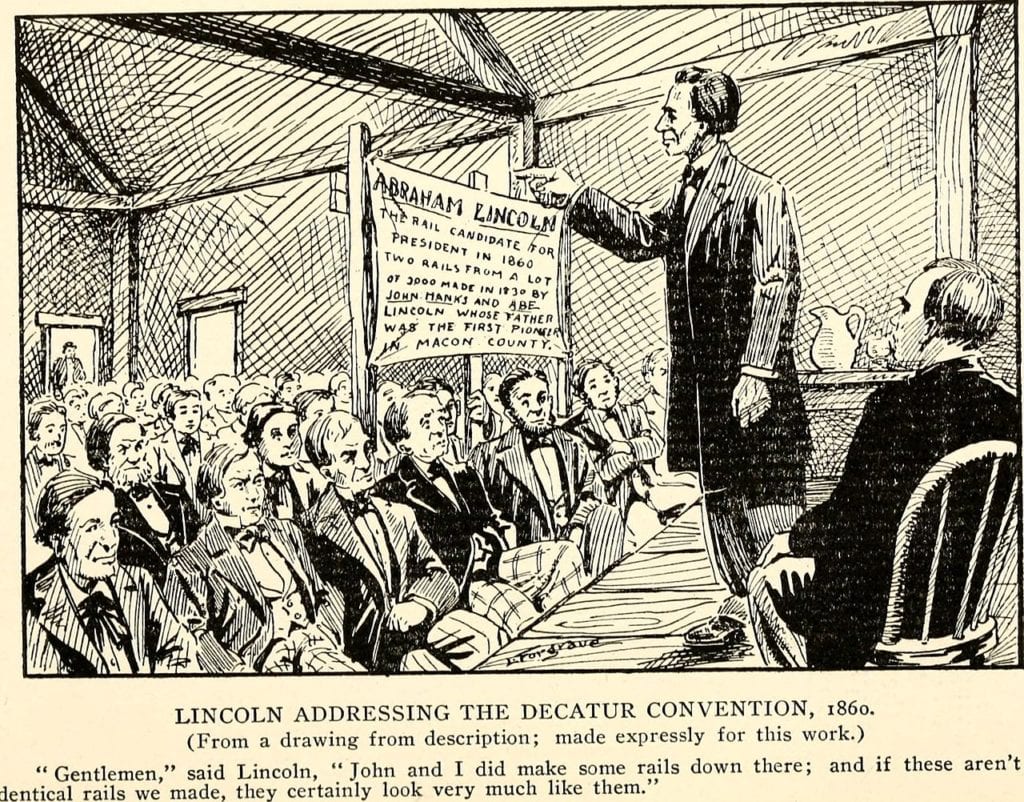

When the State Convention assembled at Decatur, Richard J. Oglesby planned and made a presentation that delighted the gathering. He asked permission to permit “an old Democrat” to bring in something which he wanted to show the convention.

Permission was granted, and John Hanks and another man entered the room carrying two fence rails that had a banner hanging between them proclaiming Abraham Lincoln “the rail candidate.” The convention called for Lincoln to enter the room. He was not far away.

Lincoln was invited to a seat on the platform, and in taking it he said that he did not know whether he made those particular rails or not; he thought they were little credit to their maker, and that he could make better ones.

Lincoln, The Rail Candidate

The rails had done their work. The convention voted solidly for Lincoln and sent its delegation to support him at the Chicago convention the following week. Backed solidly by the state of Illinois, Lincoln won the nomination in a convention that was originally more than two-thirds against him.

If it were not for the solid Illinois delegation he would not have won in Chicago; and were it not for the rails, he would have hardly won the solid support of the Illinois delegation.

He had been chopping down trees and splitting rails almost from the day his father left to Indiana, when Abraham was seven years old. This is Lincoln’s own narrative of his father’s departure to Indiana and the events occurring shortly afterward.

From the time he was eight, until he was past twenty-two, Lincoln was constantly chopping wood and splitting rails.

Lincoln’s Lesson of Success

The work Lincoln had to do was arduous and for the most part uninspiring. But he did it, and it helped to make a man of him. No man gets far in life by selecting the kinds of work which he enjoys doing and letting the rest go by. Much of Lincoln’s boyhood work was sheer drudgery; but he did it.

Lincoln was doing other things in those days besides splitting rails. He was saving pine-knots for the evening fire, so that he could stretch himself on the hearth-stone and read. He was borrowing books and reading and re-reading them.

He disciplined his mind and body. He learned the meanings of words. He cultivated a clear style of speaking. He read and wrote and thought and spoke. He cultivated to the best of his ability all his talents of body and brain.

It required all of this preparation to turn Abraham Lincoln into the man he would become. No one could have predicted the spectacular part rail-splitting was to have in Lincoln’s future, but that is immaterial. Lincoln did all the things he knew how to do that prepared him adequately for life.

He did the easy things and the hard ones; he cultivated strength of body and brain, and on the day when old John Hanks came into the convention at Decatur with those two old fence posts, the hour of destiny struck for Abraham Lincoln and the world.

We would lose the value of this story if we concluded that the only thing that made Abraham Lincoln President was pure coincidence or a clever plan by Dick Oglesby and John Hanks.

Their efforts played their part, but the convention was not as irrational as it might appear. Those two old fence rails bore mute testimony to Lincoln’s life of toil and self-development, and gave promise of large success to the man who had already risen from the position of a rail-splitter to one of the nation’s foremost men.

Those rails were a way of showing how far Abraham Lincoln had already journeyed on the road toward success. How far he was to go was left to the imaginations of the delegates and voters. Lincoln did not disappoint their hopes, or those of the nation.

Lincoln justified the enthusiasm of the convention that hailed him as a rail-splitter, and the larger one that named him as their candidate for the nation’s highest office.

Lincoln’s story of success proves to us that the man who splits rails and does it well; the man who faces his own tasks, whatever they may be, with strong determination to faithfully perform his duties, finds the results of his work, in one form or another, rising in later years to assure others of his ability, fidelity, and power.

The country made no mistake in choosing a rail-splitter as its President, and at this moment, there are others doing work just as humble, just as arduous, and just as unrelated in appearance, in preparation for heavy and glorious responsibilities in coming years.